Park Fiction @ Documenta11

“Someday, wishes will leave the house and hit the streets…. They’ll put an end to the reign of boredom and bureaucratically managed misery.” This was the leitmotif for a group of artists and musicians who joined a citizens’ initiative in 1994 in the harbor area of St. Pauli, the red-light district in Hamburg and one of the citys poorest quarters. Their goal waS tg stop plans for construction on the last remaining open spaceand to have the city build a collectively designed park instead. The campaign and the planning process that followed brought together and enriched art, subculture, and politics in unique ways. lt was not just about open space, but abeut organizing a collective process guided by the individual wishes and desires of the quarter’s inhabitants. This “wishproduction” resisted the dominant interests of economic

policy propagated by “the ImageCity” (Schäfer). Infotainment” (lectures, actions, concerts, raves, open-air movie screenings, and exhibitions) formed the basis for the planning process, reflecting the social, historical, and political importance of gardens and parks and the construction of public spaces. In order to make it possible for peopie to articulate their wishes, artists Christoph Schäfer and Cathy Skene developed various tools for the initiative: a wish

archive, a garden library, a clay modeling office, a wish hotline, a planning container, and an action kit (mobile planning briefcase). The artists also distributed questionnaires and

plans for the public to fill out.

Margit Czenki joined the Park Fiction group in 1997 to capture on film the energetic spirit of the planning process. The film shows the wide variety of wishes as well as the participants. The open planning process allowed participants to filter and combine aesthetic and practical desires with political achievement. Frequently

mentioned wishes, such as a fountain, were matched with individual plans, resulting in the “Pirate Fountain,” for example, while everyone agreed to the wish for a “strawberry tree house where grown-ups aren’t allowed.”

The planned construction was stopped. After eight Years of radical democratic urban planning and negotiations, Park Fiction is now being realized. lt is a unique example of a combination of Conceptual Art and collective subjectivity, navigating between private and public space and various cultural fields: a project in which differing interests were able to benefit each other. “The park is a utopian place; its Model is paradise…. The park shows us what the world Could be like” (film quote).“

Belinda Grace Gardner schrieb dazu in der Frankfurter Allgemeinen Zeitung:

„….Seit 1994 machen Kulturschaffende mit Anwohnern des Viertels gemeinsame Sache. Sie sammeln Ideen für eine fantasievoll-ausgefallene Oase am Hafenrand. Koordiniert wird die „kollektive Wunschproduktion“ von dem Hamburger Künstler Christoph Schäfer, der sich auf Interventionen im urbanen Umfeld spezialisiert hat. Der 38 Jährige befasst sich länger schon mit Gärten und Parks als Austragungsorte für politisches Engagement.

Kunst im öffentlichen Dialog

„Park Fiction“ ist ein gruppendynamischer Prozess, eine weitere „Erweiterung der Autonomie der Kunst“ in die Öffentlichkeit hinein. Kunst wird hier zur treibenden Kraft einer direkten Planung der Stadt durch ihre Bürger. „Die Wünsche werden die Wohnung verlassen und auf die Straße gehen“ lautet der Titel von Margit Czenkis Filmcollage, die sie vor einiger Zeit über „Park Fiction“ gedreht hat.

© AG Park Fiction: Rot soll der Brunnen von „Park Fiction” werden

Als „Tools“ für die kreative Strategie dienten der „Park Fiction“-Manschaft um Christoph Schäfer Fragebögen, die sie als „Action-Kit“ mit aufklappbarem Hafenpanorama zum tatkräftigen Ausschmücken an interessierte Bürger verteilten. Videos wurden gedreht, Polaroids gemacht, Modelle gefertigt. Und das Resultat waren wellenförmige Grünflächen mit Palmeninseln, ein grell beleuchteter „Seeräuberinnen-Brunnen“, ein Garten auf dem Dach einer Turnhalle, eine Rundbank, die die brisante Geschichte des Teehandels dokumentiert, und vieles andere mehr. Das alles wird sich in hoffentlich naher Zukunft über ein grosses Areal nahe des berühmt-berüchtigten Pinnasberg erstrecken.

Eine Utopie steht zur Diskussion auf der Documenta11

Nach langwierigen Verhandlungen mit unterschiedlichsten Behörden hat „Park Fiction“ inzwischen gute Chancen in die Tat umgesetzt zu werden: Noch in diesem Jahr soll es losgehen, wenn die Finanzierung stimmt.

Auf den Spuren von Joseph Beuys wird diese Kunstaktion unmittelbar auf das Leben einwirken und als „soziale Plastik“ in der Öffentlichkeit Gestalt annehmen.“

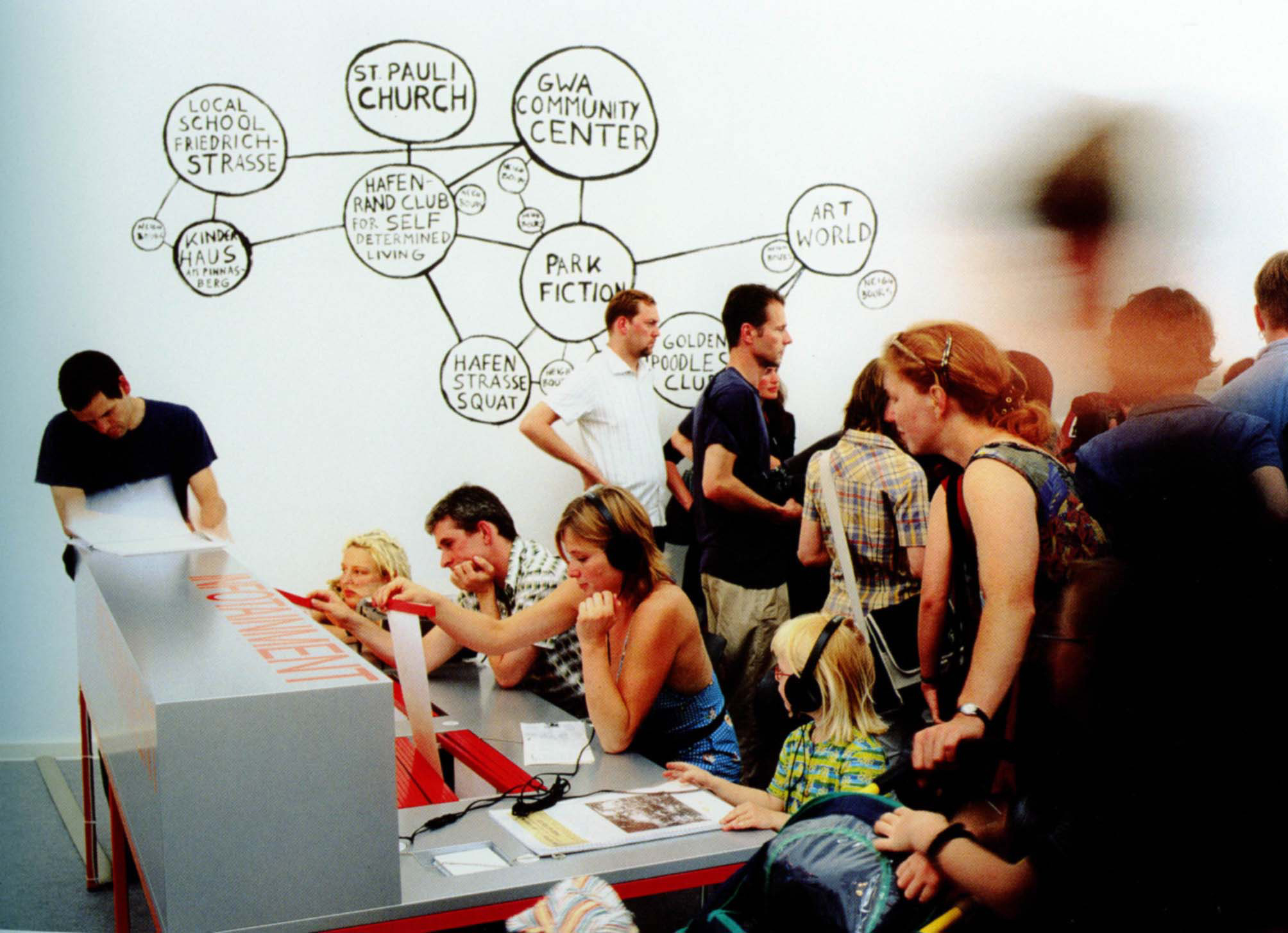

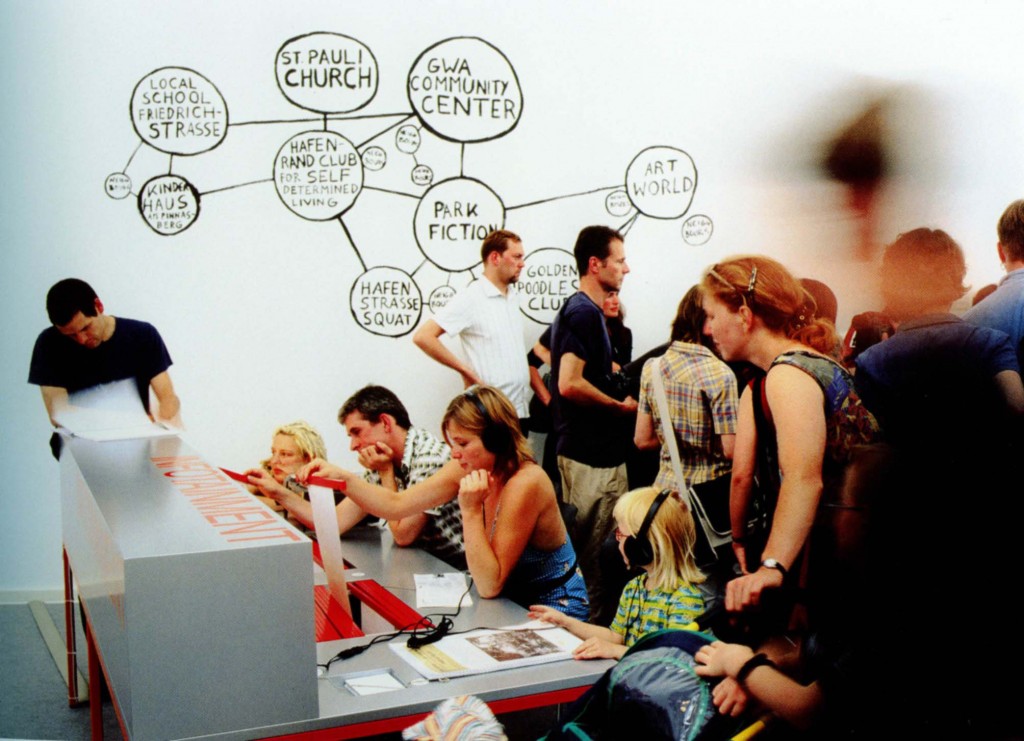

Park Fiction Installation auf der Documenta11 2002

Park Fiction Installation auf der Documenta11 2002

Miwon Kwon im Gespräch mit Beatrice Bismarck (Texte zur Kunst):

„…Aber bei der Documenta habe ich mehr bekommen, als ich erwartet hatte, und das hat mir gefallen, ich kam mir sogar wie belohnt vor. Was die Entscheidung über die Platzierung einzelner Arbeiten betrifft, habe ich keine ausreichenden Kenntnisse, um etwas über die Aufteilungen zwischen den verschiedenen Gebäuden und Orten der Ausstellung sagen zu können. Es schien allerdings, als seien kollektive Formen künstlerischer Arbeit, wie Park Fiction etwa, in der Documenta-Halle gesammelt worden, und einige Bekannte sagten, sie empfänden das als eine Art Ghettoisierung. Aber dann weiß ich wiederum auch nicht, ob nicht die Teilnahme an der Documenta in gewisser Weise auch eine Ghettoisierung bedeutet.“

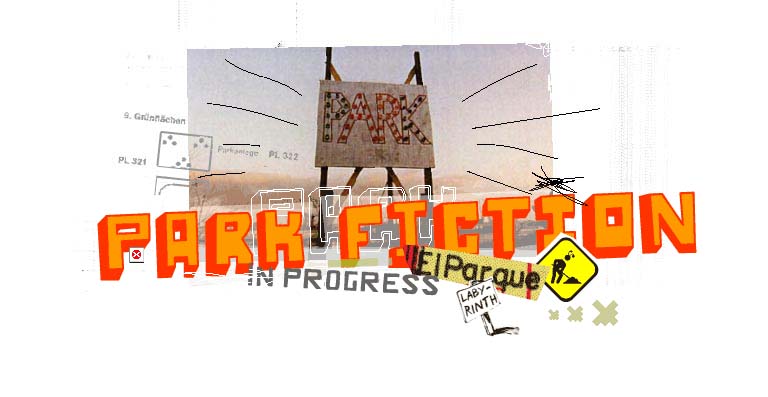

Bild: Park Fiction webseite von Thorsten Jahnke 2002

Von „künstlerisch wetvollem Städtebau“ schreibt die Deutsche Welle und denkt, Park Fiction mit Constants New Babylon, Yona Friedman und Bodys Isek Kingelez zusammen:

„Dieser emanzipatorische Anspruch treibt auch die Hamburger Gruppe „Park Fiction“ um. Unter den stadtplanerischen Beiträgen zur documenta ist ihr Projekt zudem das einzige, das auch real umgesetzt werden soll. Seit 1995 kämpft das achtköpfige Kollektiv um die Filmemacherin Margit Czenki dafür, einen Park am letzten unbebauten Stück des Elbufers in St. Pauli zu errichten – und zwar genau so, wie sich die Anwohner das vorstellen. „Die Wünsche werden die Wohnung verlassen und auf die Straße gehen“ lautet das Motto, unter dem sich „Park Fiction“ in der documenta-Halle mit Dokumenten, Bildern, Filmen und Modellen vorstellt.“

After seeing the documenta11 Installation, Brett Bloom and Ava Bromberg write about Park Fiction in the Journal of Aesthetics and Protest:

„The Park Fiction project began in 1994 when a small open patch of land with views from the St. Pauli neighborhood to the Elbe River came under threat of being sold by the city. The city wanted the space developed into high-rise corporate offices but the people living in St. Pauli wanted the space and their river view to remain unobstructed. The Park Fiction group organized to preserve the open space for use as a public park. In Margit Czenki’s film about Park Fiction, a participant named Sabine says about the project:It wasn’t just about having the park as a green area, but also about parks and politics, about the privatization of public space, about parks all over the world, about skateboarding and the pace of the city and accordingly it was about community conferences and democratic planning procedures.

Park Fiction used a variety of methods to facilitate what they call „collective wish production“, a process whereby the desires of the people of St.Pauli could „take to the streets.“ Park Fiction began a participatory design process for the contested open space parallel to the design process pursued by the city. Residents were invited to articulate designs for the park that contained elements they desired. From early on in the process the park already had what group member Christoph Schaefer described in an interview as “a social reality.” It was used continuously for public events such as open-air screenings, billboard demonstrations, and concerts. The core Park Fiction group, which expanded and contracted over the eight year course of the project, consisted of artists, musicians, and neighbors working with social institutions, the church adjacent to the park, squatters with a long history of activity in the neighborhood, and shop and café owners. A planning container on the site held an archive of desires, a garden library, and an “action kit” which functioned as a portable planning studio that could be taken to apartments in the neighborhood. Since 1997 Park Fiction’s efforts were financed by the Art in Public Space program of the municipal culture department of Hamburg. Yearly, Park Fiction held major events at the park and presented the project outside of Hamburg in international art and music circles building cultural capital for the ideas outside of Hamburg before bringing their demands to city officials. As Christoph Schaefer adds, also in Czenki’s film:

Films, performances and lectures brought art, town-planning and politics together, or rather created political discussions about art and vice versa questioned the standardized forms of political practice.

The energy behind the project was hard for one prominent city official to ignore when he attended a later Park Fiction event. When people in the neighborhood and the group became involved in widespread protests against the closing of the Harbor Hospital in St. Pauli in 1997, the city knew it had to start negotiating with the residents of St. Pauli. Roundtable discussions about the park began with politicians. After a long bureaucratic process the park, as planned by Park Fiction, is presently under construction. The project insisted on residents effecting desired changes to their environment. The result is an important landmark of successful planning from below where top-down bureaucracy traditionally dominates the decision-making processes.“