Park Fiction: Rebellion on level p

Sanssoucis

The point of reference for parks is paradise; garden art creates places of earthly joy. Parks reflect the ideals of an epoch, like the English landscape garden which mirrored enlightened humanism in the time of bourgeois revolutions. Whether it’s Alhambra, Berkeley People’s Park or Bomarzo, Lunapark or the Experimental Community Of Tomorrow in Disneyworld: parks promise a happy life free of work and removed from the routines of everyday life. To take up such a promise in St. Pauli, the city district with the poorest population in the western part of Germany, means making a subversive demand, since the ruling class attempts to teach precisely these people to come to terms with living a life in destitution, to reduce their requirements and tighten their belts. This poor-but-honest propaganda is meant to ideologically overarch the gigantic processes of redistribution. The demand for a park is a right step to counteract these policies.

Whom does the city belong to?

Park Fiction is art in public space understood as a practical critique – from the perspective of the users – of urban planning which is a manifestation and a means of state power and economic interests.

It was clear to the Hafenrandverein and the participating artists from the very beginning that artists can claim the privilege to design public space just as little as it can be accepted that the authorities and architects naturally arrogated this privilege to themselves. Especially in St. Pauli, a district that can look back on a tradition of persistent and uncompromising action against the state’s claim to control urban space – not only due to the intelligent battle over squatted houses on Hafenstrasse. In the following, we relate these urban practices to Henri Lefèbvre’s thesis of urbanisation:

Critical zone

In his book „The Urban Revolution“ / (”La revolution urbaine”, 1972), Henri Lefèbvre describes a situation of crisis, which characterises the phase of transition from an industrialised society to an urbanised society. Lefèbvre reveals lines of flight pointing a way out of this crisis towards a new form of urbanity, as within the project of the urbanisation of society the next quantum leap is imminent.

0 – 100% Urbanisation

In a first step, this concept of the urbanised society is distinguished as a correct description of the development trend from other, insufficient concepts such as leisure society or information society [because such concepts reduce reality to isolated aspects that happen to be conspicuous at the moment]. The concept of the urbanised society is the adequate description of the current development trend because the concept of ”city” also contains society, social relations, density, business and trade, production, communication, technology, history… and the materialisation of all these concepts.

The fundamental features of urban life consist in the diversity of lifestyles, the diversity of types of urbanisation and of cultural models and values associated with the conditions and fluctuations of everyday life.

The decisive point for us is that the city is appropriated space, that the process of urbanisation describes a process of appropriation.

Distinguish between top and bottom

Lefèbvre divides the city into three levels [which are not geographical], and thus describes a hierarchy: the top level [global level G] is the most abstract; it is the level of institutional power, of the state. In regard to the way they define what the city is, these institutions are either historical and outdated, like the church and the Papal State or the Greek model of the ”political city”, or they are adverse to urban life. For these institutions, city is not the goal, but constitutes the means and the locale of interests which are not identical with the city in the sense defined above. Industrialisation, in particular, has produced cities that are entirely subjugated to the instrumental rationality of the economy. In these cases the city is organised like a factory – for instance the cities in the Ruhr Region or Manchester the way Engels described it. The city falls prey to industrialisation which is given free rein by the state [level G].

This process continues today, but it has become more refined. The development of cities follows the development of capital, which consists in opening up new markets beyond actual industrial production and thus subjecting increasingly large areas of life and of the city to the logic of profit maximisation. Plain examples of this include the obstruction of urban space through cars as commodities, the systematic depopulation of inner cities in the 60s and 70s, and the transformation of once public spaces to semi-public zones controlled by private enterprises.

Rebellion on level p

The second level M [streets, squares, public buildings such as parish churches, schools, etc.] lies between level G [cathedrals, museums, motorways, barracks, airports, monuments…] and the lowest third level p [as in private], the level of dwelling space. This third level is wrongly regarded as minor. But it is precisely this level from which the changes and revolution of the cities originate.

Lefèbvre points out in detail those who cannot succeed in changing, in overcoming the critical zone – those who are not even in a position to forecast the direction it will take, and who are by no means able to develop an adequate practice: sociologists, architects and urban planners, because ”the urbanist illusion is a cloud on the mountain blocking the path”.

Instead, the revolution of the cities will start from dwelling space.

The city becomes a subject

Hoffmann-Axthelm’s book is based on this thought, which was formulated by Lefèbvre in the 70s, and on the concept of the ”3rd city”. The central idea is that the city must turn from an object into a subject. It should no longer be the object of change effected by powers adverse to it [like the global level mentioned above, like the military in Hausmann’s Paris, or the functionalist city in the wake of Bauhaus], but the subject of change – meaning that it should develop the direction out of itself and become the actor. How can this be conceived?

The revolution begins at home

Lefèbvre gives an interpretation of Hölderlin’s assertion that the ”human being” can only live as a poet. The relationship of the ”human being” to the world, to ”nature”, to his desires and corporeality is situated in dwelling space; this is where it realises itself and becomes readable. It is impossible for him to build or to have a home in which he lives, without possessing something that is different from everyday life, that points beyond itself, namely his relationship to potentiality and the imaginary. This desire is encapsulated in even the most destitute hut, the most dreary high-rise apartment in [e.g. kitsch] objects. In objects possessing exactly those qualities that modernism wanted to do away with.

From home to the streets

It is from these encapsulated desires that the vectors originate, pointing in the direction of what the phrase ‘the city turns into a subject’ means: revolution begins at home, and that’s where its direction is derived from. But – isn’t that merely optimistic speculation, a pious hope? Where are the signs of such a change taking place, of an imminent quantum leap?

The subjective factor

While in 1970 Lefèbvre quoted Nietzsche in his search for a revolutionary subject, he simply overlooked the fact that at the same time feminists put the private sphere on the agenda as being political, in theory and in practice. It was not about filling public, male-dominated, global and standardised space with female bodies in terms of equal rights for women, but about changing this space.

Quantum leaps

Then at the end of the 70s, a movement suddenly and unexpectedly arose and spread across most large European cities, expressing the desire for revolutionary change, literally taking as its point of departure dwelling space: the squatters’ movement.

At that time, high vacancy rates existed due to real estate speculation –again an example of the obstruction of urban life through an adverse power. Buildings were empty, the city was an object of speculation, subjected to profit-making interests. At that moment, dwelling space asserted its claims with force: driven by the desire to live in a different way, more than 200 buildings were squatted in Berlin alone, appropriation processes were initiated, large house-sharing groups were established, anti-authoritarian Kindergartens were founded, buildings were painted and reconstructed to meet altered needs, new music, haircuts, clothes and painting styles were developed, life was to be started anew in a different way. At the height of the battles surrounding Hafenstrasse, barricades were erected all the way into the red-light district, Radio Hafenstrasse broadcast around the clock, the city feared civil-war-like conditions – were the tattooed buildings to be cleared. And all of this was not a result of workers struggles, like those of the social movements corresponding to industrialisation, but instead, while taking up these struggles, driven by the desire for self-determined life and dwelling (or: „habiting“, as Lefebvre’s term is translated nowadays).

Recuperation

Hoffmann-Axthelm also sees this as a foresight of the 3rd city, but believes that there is no chance for this movement to continue due to the altered circumstances. The social demand for the priority of dwelling space over global powers was forced back into the homes, appropriated and marketed as a lifestyle. However, the lines of conflict were revealed, and the disputes continue in a different form.

Grossness reveals possibilities

It is precisely St. Pauli where the grossness of the facade and shop designs in the pleasure district reveals a perverted pre-view of an architecture created by the people themselves; where the possibility of a city based on desires originating in dwelling space becomes visible. Nowhere else in this country is there a district in which a class that is usually excluded from any kind of public design expresses itself to such an extent. Until now, the design of the amusement arcades, discos, striptease joints and bars, as well as numerous fairground rides at the DOM is still in the hands of small-scale businessmen, semi-criminals and parvenus. Still – because starting from the state-approved large-scale project at Millerntor, in combination with real estate speculators operating on a small scale and franchise restaurateurs, the situation is threatening to change and jeopardise the conditions for this room for manoeuvre in terms of design. Only broad resistance prevented the Harbour Hospital and the Astra Brewery from being closed down. This would have made one third of south St. Pauli available to the real estate market.

Even though the conformations and designs in St. Pauli can be criticised for being an expression of pure commodity appearance and of the fact that people, especially women, are quite obviously exploited and degraded to goods – something that is otherwise not to be seen in the uptight Hanseatic city – it is clear all the same that St. Pauli is a place where desires are expressed that in other parts of the city are banned behind one’s own four walls.

And this has to do with one of Lefèbvre’s thoughts: that dwelling space is the unconscious of the existing city.

The public sphere

Still, this says no more than that in St. Pauli there are aesthetic articulations of desires that just barely escape the homogenising grasp of state planning and bourgeois taste. But the only ones represented here are those who own or rent a pub or shop, and the motivation of these aesthetic manifestations is usually a commercial one.

What people living here lack, however, is public space unoccupied by commerce. This fact has led to the rejection of the current local development plan at Pinnasberg and the demand for a park on this site.

A brief discussion on the concept of the public sphere is appropriate here: the ‘Hafenrandverein for Self-determined Life and Dwelling in St. Pauli’ demands a park designed by the residents themselves. This points in a direction connected with what has been reflected above:

an appropriated area stands in contrast

1. to ”neutral”, public, i.e. anonymously designed urban space, as well as

2. to privatised space that pretends to be public space, but in fact functions via exclusions resulting from private property, via the racist and economically motivated expulsion of people, restrictions of activities and the motivation of certain other activities, such as buying, sitting and not lying, eating, not begging, not skating…

[The increasing private-public partnerships in the wake of privatisations unite the ugliest features of both worlds]

A park area or the largest living room in the world?

The battles described above between the global level G and level p are especially noticeable on the mid level, the level on which art in public space occurs, on squares, streets, in smaller institutions, in parks. Art in public space must therefore decide the agent of which of these two demands it wants to be.

An opportunity, a potential of resistance is given in so far as art is conceded a residual autonomy vis-à-vis homogenisation tendencies. It is questionable whether this resistance can be readily claimed in the name of an outdated concept of art based on notions of a privileged artist subjectivity. To put it differently: such a concept fixes existing exclusions, and precisely those works stemming from such an artist conception were in the 80s again put at the service of state, economic, and national interests as representational art.

Something better

The planning process is preceded by a collective production of desires in the district. The various attitudes, professions, and fields of activity that encounter each other in the process of putting through and planning the park mutually cross and infect each other. The [autonomous artist] subject is completely absorbed in a collective production of desires and a public planning process. Across common interests and concrete goals, alliances have been established between people with different backgrounds and from the most various contexts: politicised residents, social trend restaurateurs, deregulated layout men, priests, squatters, a militant female cook, hedonistic social workers, kiosk operators, geography students, and musicians from the Pudel scene. People, then, from a hedonistically oriented field with a clear proximity to level p, who situate their activities in a political/social context, a context from which they partially stem. The artists as well as the landscape architects participate in an ongoing process in which decisive demands have already been formulated. They do not work under the guidelines given or the room to move granted by state art institutions, but as members of a residents’ initiative which has empowered itself to confront state planning.

Park of accessibility, planning process of accessibility

Knowledge gained in the field of art, which can connect to the problems raised here, can create a different, additional perspective and radicalise the process. The main issue is to develop strategies for shaping a planning process in such a way that it becomes accessible for people who, due to cultural and social preconditions as well as their experience in life, are usually excluded from actively designing the public sphere. It is therefore worthwhile to take a look at those places in which private, art-like activities occur, in order to open up a space for these activities which are then not framed in a discriminating way as a hobby.

January ‘98,

Cathy Skene & Christoph Schäfer for Park Fiction working group / Hafenrandverein

based on a paper published in A.N.Y.P. 95/96

translation: Karl Hoffmann, 2003

republished in:

Will Bradley and Charles Esche (eds.),Art and Social Change: A Critical Reader, Tate Publishing UK, 2008, pp.283-9.

P.S.:

Art business !

The Hafenrandverein has been active for years. Protests against the development were already voiced in the early 80s by the St. Pauli parish; demands for a park were first made at the beginning of the 90s; and the demand for a park planned by those who use, need, and want it, was formulated by the Hafenrandverein quite a while ago. This must be emphasised again, as it cannot be tolerated that artists behave as inciters of communication [initiators] and then have the concept filled by others. This ugly paradigm shift is an avant-gardist trick with which artists, in a pseudo-modest way, withdraw from the creative field, but at the same time and in reality take on a superior position in a cultural hierarchy. These participatory artworks seem to have the purpose of absorbing the general inactivity and passivity and reproducing it as empty action.

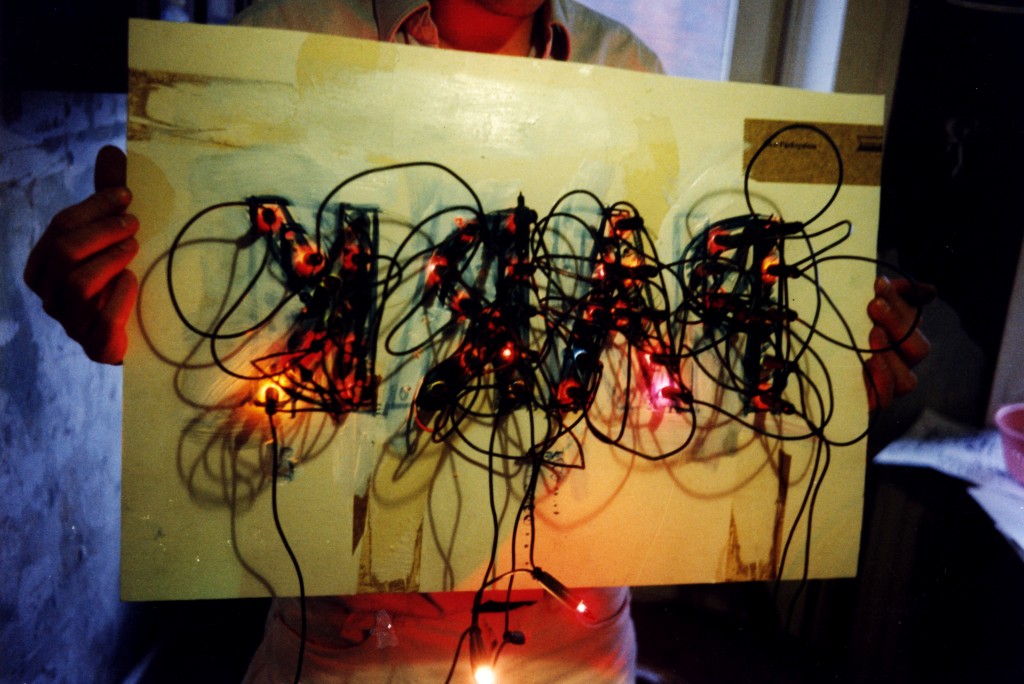

Image: Model for a „Park“ billboard, hans-Christian Dany and Christoph Schäfer, picture by Dany, 1995